We are in the midst of a revolution in gender roles, both at work and at home. And when it comes to having children, the outlook is very different for those embarking on adulthood’s journey now than it was for the men and women who graduated a generation ago.

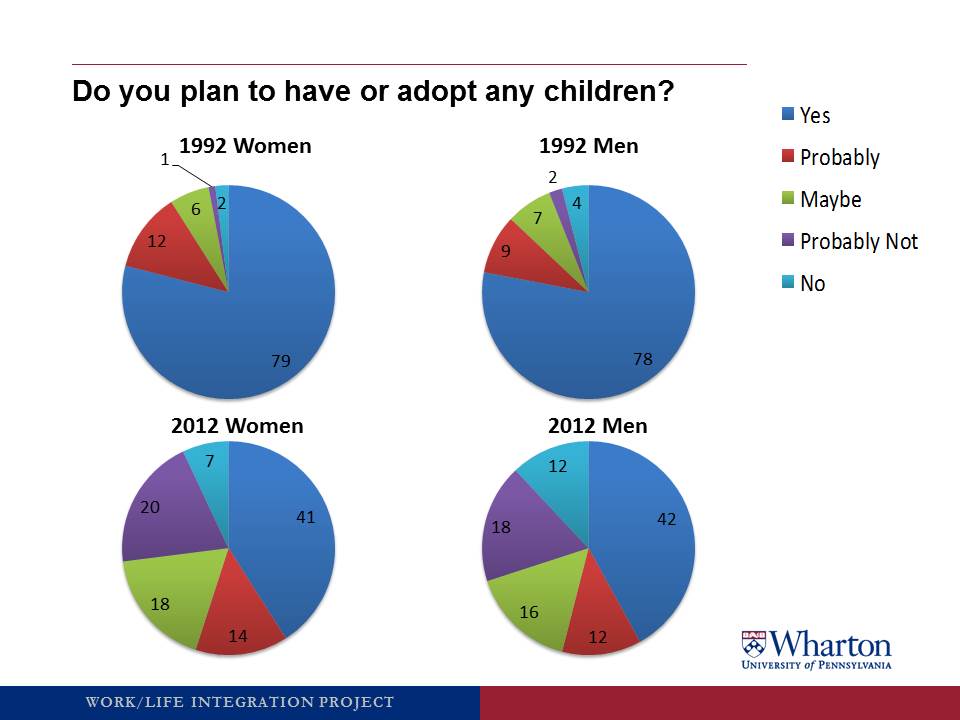

I recently published research from the Wharton Work/Life Integration Project, comparing Wharton’s Classes of 1992 and 2012. One of the more surprising findings is that the rate of Wharton graduates who plan to have children has dropped by about half over the past 20 years.

It’s worth noting that these percentages are essentially the same for both men and women, both in 1992 and in 2012. The reality today is that Millennial men and women are opting out of parenthood in equal proportions.

This change in Wharton students’ plans for parenting is part of a larger trend; a nation-wide baby bust. In 1992, the average U.S. woman gave birth to 2.05 children over the course of her life. By 2007, this number had crept up slightly, to 2.12. But, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the average number of births per woman declined during each of the four years following 2007, dropping to 1.89 (preliminary estimate) – below replacement rate of 2.10 – in 2011. The decline we observed in the Wharton study was more pronounced. While the average 1992 graduate expected to have 2.5 children in his or her lifetime – well above the U.S. mean at the time – the average 2012 graduate planned to have only 1.7.

These numbers are a bit deceiving, however, in one important way: Among those respondents in both 1992 and 2012 who planned to become parents, the number of expected children remained stable at 2.6. What caused the average of the expected number of children to plummet was the sharp decline in the portion of people who planned to have any children, through birth or adoption.

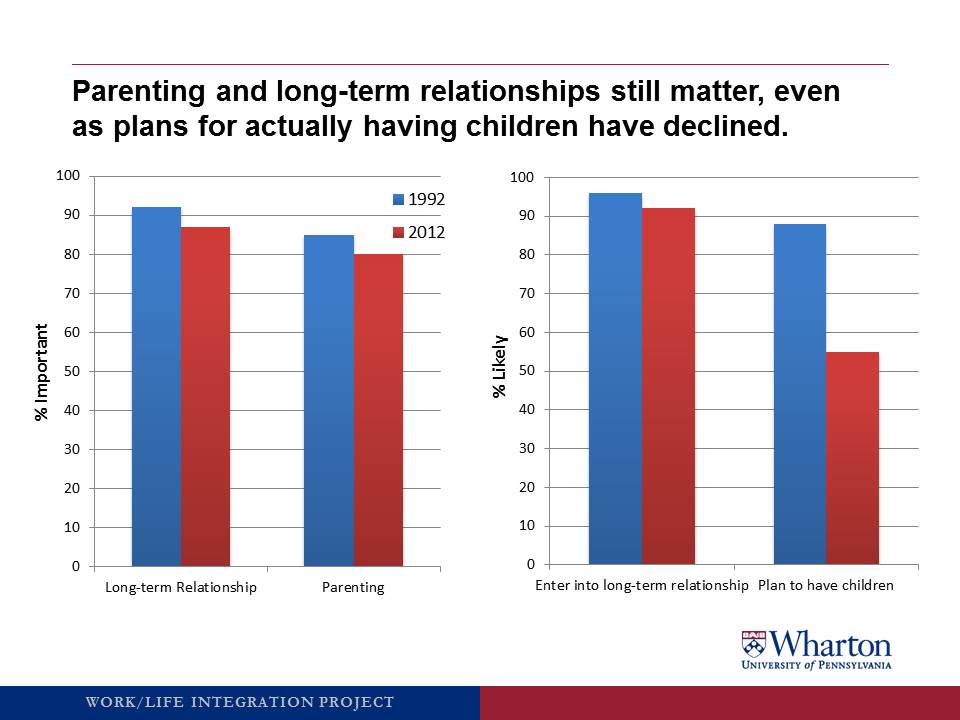

We know, of course, that not everyone wants to be a parent, but the majority still do. The percentage of people who said that being a parent is important in judging the success of one’s life declined only slightly over these two decades, from 84% to 80%.

My research, and that of others, increasingly points to the fact that the thwarting of young people’s aspirations is the result of external pressures that make having both a successful career and a child seem impossible.

Our current capacity to meet this challenge is cause for very serious concern. But there is no one solution; partial answers must come from various quarters. Here are seven ideas for action in social and educational policy, based on my own research and what others have learned:

Provide World-Class Child Care

Children require care, yet the U.S. ranks among the lowest in the developed world in the early childhood care we provide. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in a study conducted by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the majority of American day care providers ranked fair or poor and only 10% were deemed of high quality. Yet Americans spend more on child care than other developed countries, and many of those countries are able to provide excellent child care. In addition, the cost of care has doubled since the 1980s, according to the Census Bureau. Just as bad, if not worse, the K–12 education we offer falls far short of our aspirations and of global norms, and the results are distressing.

A massive overhaul could start with labor market compensation practices. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, child care workers earn even less than home health care workers. A smarter approach would be to treat those who care for children as professionals and to invest in the training and licensing requirements that would be needed to justify much higher rates of pay for those who care for our youngest citizens. High-quality child care not only helps children but enables their parents – mothers and fathers – to engage fully in the workforce without unnecessary distraction and worry.

Our 2012 respondents were attuned to the fact that children require a caring person tending to their developmental needs. This was true the men as well as women. If Millennials want children – and realize wisely that children need to be cared for and that often both parents work outside the home – then we need to step up, as other countries have done, and invest in nurturing our young.

Make Family Leave Universally Available

Family leave, including paternity leave, is essential for giving parents the support they need to care for their children. Right now, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics only 11 percent of U.S. employees receive paid family leave from employers. The one public policy that covers time off to care for new children, the Family and Medical Leave Act, laudable though it is, still excludes 40 percent of the workforce. And millions who are eligible and need leave don’t take it, mainly because it’s unpaid, but also because of the stigma and real-world negative consequences.

We need to expand who’s eligible for FMLA and make it affordable; the more people who use it, the less there will be stigma, and a virtuous circle will be created to replace the vicious cycle we have now, wherein parents opt out of work and young workers opt out of parenting. Now, FMLA applies to all public agencies, all public and private elementary and secondary schools, and companies with 50 or more employees. But the rest of American workers are not eligible for the 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave. In other developed countries, family leave is available and it is paid.

The Millennials in our study, including young men, wanted to be engaged, loving, and present parents, but they could not see how they could make this work economically. The FMLA is a resource that provides them with the support they need.

Revise the Education Calendar

The standard school day is based on an outdated schedule. Other countries have children in schools for longer days and for a greater part of the calendar year, providing support for working parents and enrichment for children. Friedman’s The Measure of a Nation indicates a correlation of nearly 90% between the number of school days and the results on a world-wide measure of reading, math and science. Revising the school calendar would be a benefit to children, to working parents, and to organizations that would, in the long run, have a better prepared workforce. Having children in school longer hours and for a greater part of the year is yet another way we as a society can help support young dual-career families so that they can envision a way of having their family and work lives in harmony rather than in perpetual discord.

Support Portable Health Care

In our study, the anticipated financial costs of childrearing negatively affected Millennials’ plans for becoming parents. Given the rising costs of health care, working parents benefit greatly from health care policies that don’t punish them for taking time off or moving. The Affordable Care Act is a step in this direction. It helps families obtain care while avoiding crippling debt as both parents might now have to navigate careers in which they move from job to job. And preventive care reduces the need for time off due to health problems that afflict workers and their children. This is yet another way that we can ease the burden for those young couples who want to have children and two careers.

Relieve Students of Burdensome Debt

Many young people simply can’t envision a future in which they can afford to support children because they are carrying high levels of student debt. Skyrocketing interest rates on student loans and the increasing cost of higher education result in debt burdens are too onerous. Chris Christopher, senior economist at IHS Global Insight, calls student debt “a real monkey wrench in the works of our families and economy,” adding that if college costs and student debt continue to rise, the nation’s low birthrate may become the “new normal.”

Nobel-laureate economist Joseph E. Stiglitz concurs. “Those with huge debts are likely to be cautious before undertaking the additional burdens of a family,” Stiglitz writes. What’s true nationally is also true of the Wharton men we surveyed in 2012. Those men who told us that they had financed their undergraduate educations through employment during school, private loans, government loans, and scholarships and grants were significantly less likely to plan to have children.

Display a Variety of Role Models and Paths

In our sample, we found that career paths have narrowed because students believe that they must earn money quickly and that only a few options offer this. One man from the Class of 2012 said, “Career paths today seem to be pushed upon students too quickly, or students find themselves in paths they don’t feel are expressing their true selves but are ‘stuck’ due to financial reasons.”

The more that young people hear stories about the wide range of noble, and economically viable, roles they can play in society, the easier it will be for them to choose the roles that match their talents and interests. Young adults would benefit from exploring as wide an array of career alternatives as possible, including and especially those that allow them to have the kind of autonomy and flexibility required to be engaged in both their careers and in their roles as parents.

Require Public Service

Our study found that young people today, especially women, want to do work that helps others, despite their expectation that they will not be well compensated for it. And young women who expected their jobs 10 years in the future to provide the chance to serve others were significantly less likely to plan to become mothers. Young people are yearning to do work that benefits others. Our society could channel that enthusiasm and idealism by requiring a year of public service for postsecondary school youth, which would not only improve our workforce but would help all of us recalibrate what’s really important. And it might help those young women who, as we observed, now foresee a tradeoff between social impact via one’s career and motherhood, to envision instead a life in which they can serve both the family of humanity and a family with children of their own in the scope of their lifetimes.

There are a lot of unknowns about what our current birthrate means for business. Some argue that in our neo-capitalist society, based as it is on information and finance, there is need for a smaller but more productive labor force. Families no longer need their children for farmhands and so society, and our increasingly automated manufacturing sector, no longer has the same demand for labor. On the other hand, an aging population with fewer workers could mean trouble sustaining social-security programs, projecting military power, and maintaining a high degree of innovation.

But what we do know is that families centered on a single-earner father are no longer the norm. And yet our current institutions are still based on this outdated model. We, as a nation, need to focus on what children in our society require – nurturing. How can they get it if we do not provide the essential social and educational support that working parents need?